Experiments with Monte-Carlo dropout for uncertainty estimation

- 6 minsIntroduction

Imagine you created a deep learning model which can classify cats and dogs. You collected various cat images but you could only find sausage dogs for the other class. Your NN is trained and evaluated (reaching pretty nice management compatible KPIs), production ready we could say. But after the deployment the NN meets with the first non-sausage dog image, a Labrador. What should the model do, what is the proper output? Just think about this for a few seconds.

When you train a classifier the prediction produced by the model is just a label and most probably a softmax score. Some of the people use this softmax score as the “confidence/certainty” of the result (- “if it is 0.8 then my model is 80% certain about it’s prediction”). This is problematic as NNs tend to be too confident and it can output high softmax values while it is uncertain [3].

In a scenario when our model meets with a new kind of dog, I would expect my NN to tell me - “looks like a dog but I am not sure” or just “I am not sure, please check”. This is called epistemic uncertainty, which comes from the lack of knowledge [1]. This can be improved by collecting more relevant data [2]. (In our example the researcher should collect different kind of breeds of dogs.) At the same time we can have a prediction like “I don’t know” and this can be reached by variational inference. I won’t write about the theoretical part of VI, as you can find a lot of materials, but trust me, Bayesian approaches compared to frequentist deep learning are (computationally) expensive.

This is why I really liked the Monte Carlo Dropout concept which says that a NN which contains dropout layers can be interpreted as an approximation to the probabilistic deep Gaussian process [3]. This means that you won’t need new architectures or training methods, it works almost out of the box as long as your model contains dropout layers. With that being said, let’s get to the experimental part where I tried it out to see how it works.

Uncertainty estimation

The question comes. What should I do to receive an “uncertainty score” for the predictions?

Take a model with dropout layers and then activate those at inference time also, forcing the network to mask certain connections. Now you just need to perform inference on a single input multiple times and record it’s outputs. From the gathered data you can calculate the mean and variance (or entropy for classification tasks) of the predictions, which gives you the uncertainty.

I can hear your thoughts - “but what is uncertainty? Standard deviation $0.5$?, Entropy $0.1$?”. This is something which you need to define, and create a metric and the logic in your application as a post processing step.

Experiments

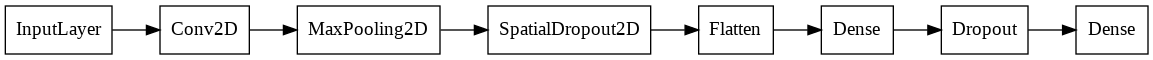

I created a model which contains spatial dropout after every convolutional and a simple dropout after every fully connected layer but the last one which provides the outputs.

Spatial dropout is needed as I work with a convolutional network and masking single connections is not effective as it does not remove enough semantic information. But masking whole feature maps (or regions) can force the network to learn from remaining maps. This produces a more diverse set of features [4].

You can make the dropout layers active during inference time:

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.5)(x, training=True)

For the data I choose the MNIST dataset without any augmentation and then trained my network.

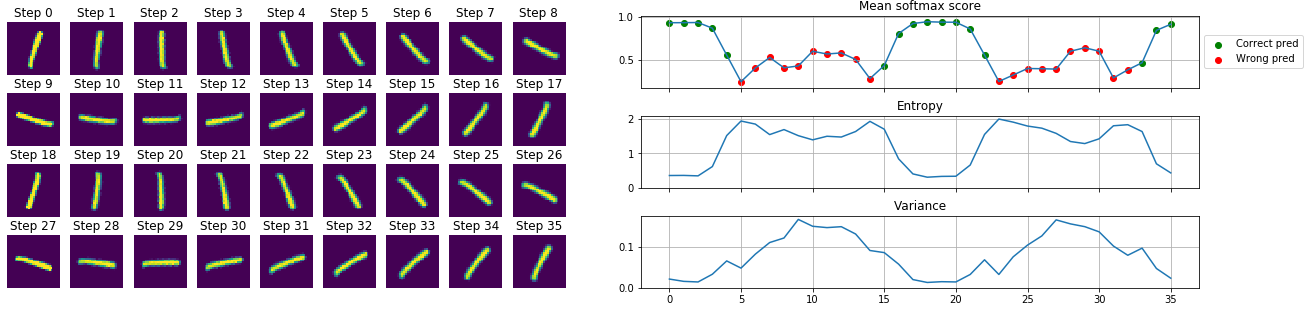

For every experiment I choose a random image from the test set and then transformed it through multiple iterations to see how the prediction and uncertainty varies. Every transformation step the image is fed to the network $N=1000$ times, then I calculate the softmax score mean, variance and entropy.

- Variance: $\sigma^2=\frac{\sum_n(x_n-\mu)^2}{N}$

- Entropy: $H \approx - \sum_c^{C}(\mu_c)log(\mu_c)$ where $\mu_c=\frac{1}{N}\sum_n p_c^n$ is the class-wise mean softmax score

Rotation

In the following experiment an image with the label $1$ was selected and then rotated with $10$ degrees at each step. On the plot below you can see how the metrics vary for the different images. When the image is rotated $90$ degrees, the network outputs a different label than the original, but the variance is high. This can be a trigger that the model is just guessing and actually does not know the answer.

The same experiment with an “MC Dropout free” model, would produce only the top softmax value plot. This is problematic as with a carelessly selected softmax threshold (let’s say with $0.5$) we can introduce false detections when it would be much better to say “I don’t know”. (The plot below illustrates this at steps 10, 11, 12, 13, 28, 29, 30).

On the following animation you can see the histogram of the collected softmax outputs (from $N=1000$ inferences) for the different classes. Red marks the true label, and the highlighted histogram is for the class which is the prediction (np.argmax(np.mean(softmax_outputs, axis=0))) of the model at that step.

Blending

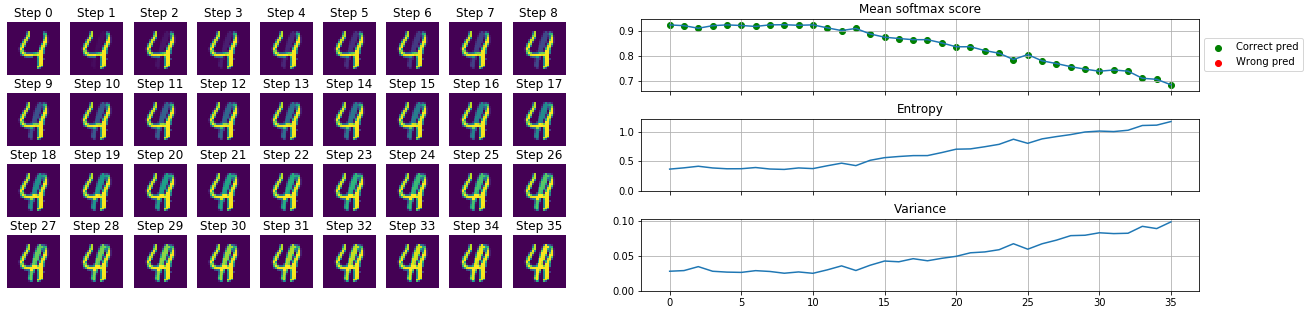

2 images are selected and we start to blend them: $combined_n = image1 + \alpha_n image2$ where $\alpha \in [0,1]$ and $n = 0…N$. In our case the label $4$ is the “dominant” number and the $1$ fades in, which is rather interesting as the location of the $1$ is almost at the stem of the $4$. I think because of this phenomenon our model correctly predicts the label all along (the softmax values, drops from $~0.95$ to only $~0.7$), but with an increasing uncertainty.

As a human around step 15 I would not be confident to label the image as a $4$.

Also on the animation we can see how the bins for the $4$ start to fill up as the $\alpha$ value increases and the $image2$ becomes more dominant and the network becomes more uncertain.

Conclusion

In this post you could see why it is important to know more than the softmax score for classification or just a prediction for regression tasks. With a prediction mean and variance you can tell much more about your model’s behavior.

The drawback of the method is that you need to make multiple inference steps with the model to calculate meaningful variance. We also should not forget that our NN is still dependent on the dropout and activation hyper-parameters which can modify the calculated uncertainty.

Overall this is an interesting and lightweight approach to estimate prediction uncertainty, which I will use in future projects for better filtering options.

References

[1] - Aleatory or epistemic? does it matter?, 2009

[2] - Single-Model Uncertainties for Deep Learning, 2018

[3] - Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning, 2015

[4] - Confidence Calibration for Convolutional Neural Networks Using Structured Dropout ,2019